Folders |

Backstage With Untold Track and Field History: After Legendary New York Sprinting Career, Mike Sands Becomes A Pillar Of Bahamian AthleticsPublished by

New York Sprint Star Mike Sands Still Carries the Bahamas Flag As the World Relays Are In The Starting Blocks By Marc Bloom Part Two | Part One After the divisive 1968 teacher’s strike was over, and things settled down, Mike Sands began his new life in Brooklyn, at Sheepshead Bay High. The challenges he would face in fending for himself as a 15-year-old newcomer from the Caribbean were met with Sands’ unerring resourcefulness. He handled whatever came his way with aplomb, delighted with his new environment, expecting nothing other than a chance to grow. On the soccer team, Mike was thrilled to have a uniform for the first time. Playing center half, he showed spark on the field. Word got around. After the season, he signed up for indoor track. Sands had never run indoors. He certainly wasn’t built for it. At 5-feet-11 and 195 pounds, Sands was already fully grown. How would he handle a sharp, slippery indoor turn? Like many city teams, especially those with no outdoor tracks, Sheepshead, during the winter, trained in the school hallways. In the narrow corridors, two or three runners at a time would tear out in some makeshift configuration, doing the equivalent of repeat quarters, or whatever was set up for the day. The Sheepshead coach, Stu Levine, used the first floor, sending athletes in loops around the outside of the auditorium. On Sands’ first day, Levine had him race his top sprinter down a hallway. Mike won. Then, Levine had Sands race his next fastest guy. Mike won again. Levine told him, “Do you realize you just beat my two fastest sprinters?” Mike was more impressed when he was given his track uniform — a second uniform! Levine also gave Sands a grand tour of the practice loop, showing him how to lean in with his large frame around the sharp corners that defined the square-like auditorium compound. Mike at 15: New home. New country. New school. New family: the track family. “I was not afraid to meet new people,” Mike told me. “It was like when I sold newspapers on the streets. I met everyone.”

At the indoor season opener, the Bishop Loughlin Games, at the New York Armory on 168th Street, Mike was instructed not to slip on the old wooden floor because “the splinters will eat you.” His future rival, Steve Williams, could attest to that. In one meet, in a 440, Williams had to lunge across the finish to win by a shade, splattering to the barn-like wood. Later that day, Williams had to be treated at a hospital to get his bloodied legs patched up. Sands won his first race, the novice 100 yards, “breaking his novice.” (At the “old” Armory, the 100 was run end-to-end, not around the oval; the start was at the entrance where you walk in today from the outer corridor, and the finish near the current throwing cage, off the far turn.) The flooring, cobbled together decades earlier for military maneuvers of the National Guard, did not accommodate starting blocks. No spikes either. For token traction off the start, sprinters would affix strips of grip-like tape to the wooden surface, or use a “stick-on” spray. Once in flight, the sprinters, at top speed, would have to negotiate the turns with surgical care, a delicate dance of timing and body position. It would be two years before Sands would learn a hard lesson at the Armory running against his two great high school rivals — the aforementioned Steve Williams, a future world record holder, and his namesake, Harold Williams. For now, Sands emerged from his first winter campaign and into the spring poised for breakthroughs. At the PSAL outdoor city championships, he placed second in the 220 yards contested on a long straightaway, as many were in those days. Sands ran 21.6, one-tenth shy of the winner. The time made Sands the fastest sophomore in the state by a half-second, and was only one-tenth off the state sophomore record of 21.5 held by the legendary Julio Meade. “Mike was a man among boys,” a teammate, James Shipley, now living in Florida after a career as a TV, film and Michael Jackson world tour cameraman, told me. “All muscle, and a straight arrow. We tried to emulate him.” As a young coach, Levine was picking up ideas from any source he could. Warner, ahead of his time, would feed him training manuals and talk about Lydiard and sports psychology. Warner studied “Athletics Weekly,” from Britain, and, in a tenuous understanding with Levine, coached some of the Sheepshead distance runners himself. Sands appreciated Warner’s engagement. For my 1971 Letterman story, Sands told me then, “He tells me things that make me think about fundamentals.” Warner was always whispering in Sands’ ear. “He was like my Bundini,” Sands said when we spoke recently, referring to Muhammed Ali’s cornerman, Bundini Brown. “He brought a level of comfort. I never questioned anything he said.” When I reached out to Warner, now a distinguished college professor of philosophy in Chicago, he told me he’d tried to help Sands relax his big muscles by “freeing” himself from external stimuli and running as “naturally” as he could. Warner came up with a mantra for Sands. Warner had a girlfriend, Lisa. When Sands settled into his blocks for a sprint, Warner would offer, “Lisa says good luck, and run free.” How’s that for sophisticated sports psychology? Levine, then in his mid-20s, was the ideal mentor for Sands. Levine was soft-spoken, a man of few words, able to distill complex concepts into their basics. Serving as Mike’s surrogate parent, Levine, now 80 and living in central New Jersey, reinforced Mike’s values and humility, affirming his desire to eventually return to the Bahamas and help his people. Levine’s paramount message was: schoolwork first, track second. Once, Levine felt his policy abused. It was in Mike’s junior year, during the indoor season. Levine found out Mike had cut classes and suspended him for a week. When Levine confronted Sands, he offered no excuse. Levine told me that Mike might have been hanging out with the wrong crowd. It was a tough time for Sands. His cousin in Crown Heights had a boyfriend, and to make room for her gentleman caller, Mike was asked to leave. The school guidance counselor found temporary housing for Sands in a home for wayward boys in a bleak part of Manhattan. Sands was there for a few weeks and, except for that one time, never missed school or practice. Still, his life was in disarray. For a lift, he frequented the movies in Times Square. Both Sands and Levine had foggy memories of the episode. When Levine visited the halfway house, he broke down, seeing what Mike had to go through. “It was a dark period,” Sands said. “I’ve tried to blot out the details.” Soon, the cousin’s boyfriend was on the outs and Sands was allowed back into the apartment. Bolstered by a return to normalcy, as a junior, in 1970, Sands fashioned a gaudy track season. He captured the PSAL city titles in the 100 yards indoors, in 10.1, and 100 outdoors, in 9.8. Winning a city sprint title during New York’s “Golden Era,” was like crafting a “Connie Hawkins” at Rucker Park in Harlem. Sands’ start, with his size, remained flawed. “I knew the first 20 to 30 yards would be a disaster but I didn’t dwell on it,” he said. “I worked on what they now call the ‘drive phase,’ trying to be close enough by 50 and let my top-end speed take me through.” After the regular high school season ended in late May, Sands, soon to turn 17, was selected for the Bahamas British Commonwealth Games squad to compete in Edinburgh, Scotland, in late July. Sands had two months to prepare. After the aforementioned dispute (part one) with the Bahamas team coach was smoothed over, Sands used Levine’s workouts, designed to sharpen him up for his first major quarter while being careful to protect his injury-prone muscles. Like most sprinters, Sands had resisted running the 440, or 400 meters, in fear, as he told me, of “rigging up.” All through his junior year, the quarter had been a hard sell. Levine tried to ease Sands into it with a leg on a distance medley relay. One time, Sands’ 48.8 split gave Sheepshead an insurmountable lead. A rival coach told Levine, “I never saw a distance medley won by the quarter-miler.” By the summer, in the Bahamas, with Levine’s training behind him, Sands made the quarter his own. He raced the 400 meters in 47.5 in a tune-up meet for Edinburgh. He also ran the 100 yards in 9.5, 100 meters in 10.4 and 200 in 21.4, all in July. On the U.S. high school lists for 1970, Sands was tied for second among juniors in the 100 yards, and tied for third among juniors in the quarter. In Scotland, Sands tried to frame his first major championship as just another meet. He was set for the 100, 200 and 4x100 relay. He didn’t let it phase him that he was mixing with luminaries like Don Quarrie, who would take both sprints, and other Caribbean stars like Lennox Miller, Edwin Roberts and Hasely Crawford. After being eliminated in the 100 heats, Sands lined up for the 200, the better of his two sprints, less dependent on his start. But his upper right leg muscles had other plans. Sands pulled up on the curve in pain and was carried off the track on a stretcher. Returning to Brooklyn to mend for his senior year at Sheepshead, Sands did not dwell on a lost opportunity but, instead, relished the idea, as Levine suggested, of running cross country to build himself back up. When I asked Mike how he could shrug off such a public failure, he said two things that seemed paradoxical: “I was oblivious. I didn’t grasp the magnitude,” and, since he had been on his own since 15, “I had already lived life…” This was the beauty of Sands from day one — the professed innocent with a courage borne of getting around. He would make that world-weary hunger work for him. But, an almost 200-pound sprinter running cross-country? At Van Cortlandt Park? Sands’ leg was bad and first needed weeks of rehab. He went to the reputed Brooklyn chiropractor, Doc Goldstein, who told Mike the injury was to the vastus medialis, part of the quadriceps. Eventually, Sands could jog and put in some mileage, all keyed to the track season. Before the fall campaign ended, Levine, with impetus from Warner, stuck Sands in a J.V. race, 2.5 miles, at Van Cortlandt. With the brashness known to every sprinter since the beginning of time, Mike burst out in the lead going into the woods. Then the hills came. Then Mike walked. Mike told me that with his come-what-may attitude, his kids, even as adults, would say to him in wonder, “Dad, we never see you sweat.” This day in the Bronx, Mike Sands sweated. The rest of his race was a walk-run endurance test to the finish. “We had to wait for him,” recalled Levine. Mike ambled in, impervious to embarrassment. “I didn’t take it seriously enough to be upset by it,” he said.

Sands would get the last laugh. In a rare admission, Mike told me, “I was nervous. It was the unknown.” Levine told him, “Just pace yourself.” Of course, what else? Sands proceeded to peel off a 2:02. That was Julio Meade territory. And maybe some kind of indoor record for a high school sprinter. Sands’ summary: “I never limited myself.” Back in his wheelhouse, Sands was joined by Steve Williams of Evander Childs in the Gun Hill section of the Bronx and Harold Williams of Newtown, in the Elmhurst section of Queens, for the full range of sprint events. It was a sprint trio the likes of which was practically unprecedented. Sands would prevail all season but twice, once indoors and once outdoors. At the Armory, Sands’ best races were his 49.8 440, No. 2 in the nation that season, decisively over Steve Williams, and his 31.8 300 yards, fastest in the country. Sands’ strength work was paying off. It gave him the confidence to go out fast and make people try and catch him. The 300 time came in a heat at the Eastern States meet. In the final, Mike, Steve and Harold lined in the “hole.” “Mike was intimidating,” said Steve, when I reached him living in the Bay Area. “He was like a fully-grown man.” The antagonists were of three different body types: Burly Mike, 5’11” and 195 pounds, Steve, a stringy 6’2” and 153 pounds. Harold somewhere in between, at 5’11” and 175 pounds. “I was all legs,” said Harold, now living in the Dallas area after many years in California. Only Harold could recall what happened next. “We were three abreast,” he said. “When we hit the turn, something had to happen.” He continued: “Mike and Steve were in the two inside lanes; I was on the outside and got a good view of it.” It should be noted that the Armory track had no defined “lanes.” Where you ran, that was your lane. Mike took an elbow from Steve. As Harold put it, “Mike was knocked off his race. Redirected.” It was not intentional, just too many arms and legs seeking the Armory sweet spot at once. Steve pulled away to win in 32.2. Harold got second in 32.5. Mike, humbled, trailed in 32.8. Outdoors, Sands ran 48-flat in his first individual outdoor 440 in a Sheepshead uniform, doubling with a 21.6 220. In probably his best in-season high school race, Sands captured the PSAL city championship in 47.2, at Randalls Island, then the fastest time in the country. It still irked Levine that Sands went out a touch too fast. His 200 split was usually 22-flat. The next week, at the Eastern States championships, Sands turned to the 220, winning in 21.2 over both Steve and Harold. One notable spectator was so impressed that he came down from the stands and onto the track to congratulate Mike. “You’re a big dude, you remind me of me,” John Carlos told him. And, by the way, “don’t lean forward so much.” Sands would get to know Carlos and invite him to a symposium in the Bahamas years later. Sands’ one outdoor loss that spring came at the Eddy Games in upstate Schenectady, a meet that always drew a significant New York City entry. Harold won the 100 in 9.7 with Mike and Steve second and third, both in 9.8. Even in defeat, Steve considered that race a breakthrough. So much so that over the summer, he would run 9.4, tied for the fastest time in the country. Likewise, Harold won his second straight national Junior Olympics title in 9.5. Sands also recorded a 9.5 as well as a windy 9.3 and legal 20.9 220 on the turn, second behind Marshall Dill of Detroit in the International Prep meet in Chicago. Assessing his times in all three sprints, Track & Field News declared Sands the best all-around sprinter in the U.S. that season. Putting Mike together with Steve and Harold in a tri-borough collective, it was clear that, in 1971, New York was Sprint City. With his 47.2 440, Sands was one of the favorites for the Golden West national championship the next week in Sacramento. All of us made the trip with Mike: coach Levine, Warner, and me. I’d helped the meet with its Eastern entry and had covered the event almost every year since ’66. For the four us, in California, in the brilliant sunshine, engaged with the national community, it was like a graduation party. We adults could summon the thrills of “our” young man who’d done so much and feel great anticipation for what lay ahead. However, a national title would have to wait. When it came time for the 440, Sands tore out first on the Sacramento State track. But he was devoured on the home straight by a great closer, the California state champion, Tony Krzyzosiak, in 46.9. Sands placed fourth in 47.5. Looking back, Sands admitted he went out too hard. He also said he was disoriented by the design of the race, in which he confronted a “California start” for the first time — the field finishing at the top of the turn as opposed to New York style, in the middle of the track. While the defeat may have seemed like unfinished business, on the flight home Mike’s maturity stood out, his aura intact. It was Father’s Day. As a gesture, the flight attendants went down the aisles giving gifts of nicely-wrapped packaged cake to fathers, or those pretending to be. Mike and coach Levine were sitting together. Ignoring Stuie, the stewardess handed a cake to Mike. “Mike looked older than me,” said Stuie, then 27. Stuie told the stewardess, “Actually, I’m the father and this young man is my son.” The stewardess shrugged. Mike kept the cake. Colleges from coast to coast had offered Sands the moon. Recruiting was then the Wild West. NCAA rules were, to some, a joke. One school that jumped on Sands was UTEP, not known as a bastion of propriety. Both of the Williams boys had committed to UTEP, spent a fractious year in El Paso, then left for San Diego State. Levine advocated for Penn State. So did Mike’s club coaches at the New York Pioneers, Joe Yancey and Ed Levy. So did Penn State freshman Fred Singleton, the 1970 Golden West high hurdles champion from Mt. Vernon, who Sands knew well. State College, it would be. Singleton (who would later coach Mt. Vernon rival White Plains High for 49 years to this day, and serve as the long-time Loucks Games meet director) lured Sands, who’d had enough of cold winters and training in hallways, with promises of an annual spring break track trip to Florida and warmer climes in central P-A. Once enrolled, Sands realized there would no such trip. For months on end, he froze his tush. Winter training was on a bandbox track above the gym, or around an indoor skating rink. Despite the limitations, Sands, as a senior, captured the 1975 NCAA indoor title in the 440, running 48.5 at Cobo Hall in Detroit. In the NCAA outdoor, at BYU, Sands set a stadium record, running 45.46 in the semis but much slower in the final, taking fifth. Sands told me that his muscular legs would build up an excess of lactic acid, often resulting in faster times in heats than finals, and making same-day doubles difficult. He had to do long warm-ups and wear two pairs of sweat pants to loosen up. At the 1976 Montreal Olympics, on the same day, he ran the 400 heats in a runner-up 46.52 to move on, but only sixth in the quarters, in 46.48. He was also dealing with an injury and, as well, continuing friction with the clique of autocratic Bahamas coaches. They dug up reasons to charge Sands with “insubordination” and send him home from Montreal — even though Sands had been the flagbearer in the Opening Ceremonies. Sands summed it up to me as a “communications breakdown.” By this time, ironically, Sands was fast becoming a national hero, a pioneer in Bahamas track and field heralding a new era of major medals for the small Caribbean country situated a short hop from the U.S. mainland. Any coach with a big chest and a parochial bent might have had a problem with a “local” athlete’s assertiveness. “I was not being defiant,” Sands told me. “It was just me. The coaches never understood the real Michael.” Bahamas, a popular U.S. cruise destination, is comprised of numerous islands, with some private idylls owned by American celebrities like Johnny Depp and Eddie Murphy. In the mid-seventies, it had about 200,000 people (the population has since doubled). The capital and largest city, Nassau, is located on the island of New Providence, the country’s commercial hub, a small speck of land — 21 miles by 7 miles — even by Bahamas standards. The nearest Bahamas island to the U.S. mainland, Bimini, is only 50 miles away, due east from Miami. In 2023, Bahamas commemorated a half-century of independence from the British Crown.

At the time, neighboring Jamaica, bigger and far more populated, already had a prominent track history, with early stars like Arthur Wint, Herb McKenley, George Rhoden and George Kerr. With its track-centric glamour, in 1975, the capital, Kingston, hosted the seventh International Freedom Games, previously held at Villanova, Philadelphia (the ’71 Liquori-Ryun “Dream Mile”) and Oslo. Sands, finishing his senior year at Penn State while receiving his degree in health administration, was invited to Kingston for the 400. Many fields were of Olympic caliber. However, Sands was told by his coach, Harry Groves, that the trip was disallowed; the University would not foot the bill (meet expenses were committed to athletes from Africa). Sands appealed to the Dean of Students. It was not a cold call. To have some money in his pocket, Sands had mowed the lawn and shoveled snow at the Dean’s house. He earned five bucks a pop. Sands suggested to the Dean that his appearance in Kingston would bring honor to the University. “I think I can win,” Sands said. “Leave it to me.” Impressed, the Dean gave his blessing, expenses included. When Groves got the news, he approached Sands with glee, telling him, “We’re going to Jamaica!” To which Sands responded, “What do you mean we?” In Kingston, with Groves in tow, Sands, at 22, won the 400 handily in 45.20, his lifetime best. It was a Bahamas national record that would stand for 21 years. Still going out hard, Sands, then 6’1” and 197 pounds (with 4 percent body fat, tested in the Penn State lab), burned the first 200 in 21-flat, winning by five yards. Afterwards, he told reporters, “I still don’t consider myself a quarter-miler.”

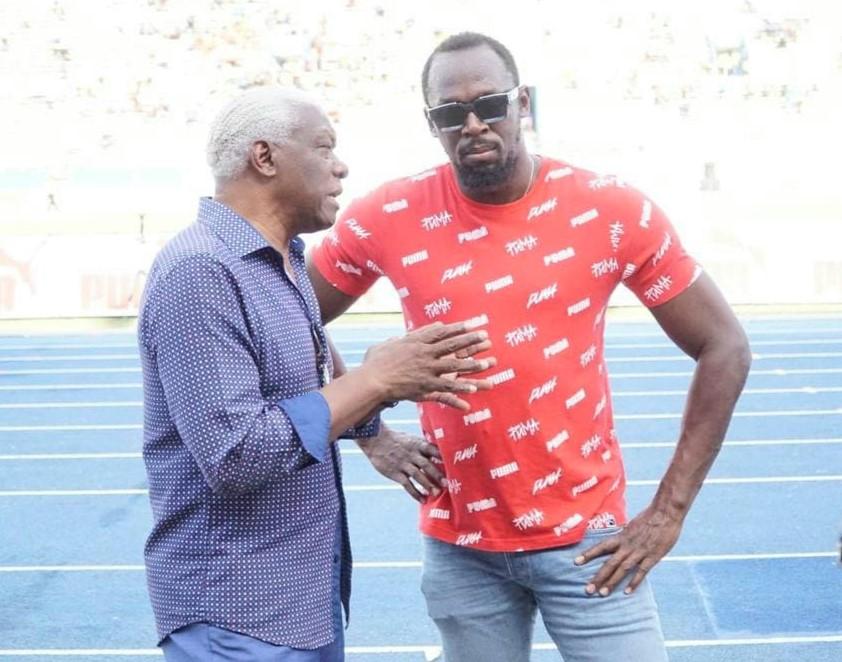

In Kingston, Williams, 21, captured the 100 in 10.0 and 200 in 19.9, then the greatest sprint double ever. In both races, he defeated the local hero, Don Quarrie, the next year’s Olympic 200 champion who also took silver in the 100. Only a few years late of pulling Armory splinters from his long legs with a tweezer, Williams would set or equal world sprint records at least six times. His lifetime bests, all hand-timed, were 9.9, 19.8 and 44.9. “I was an All-Terrain Sprinter,” Williams told me. “I ran in pouring rain, on dirt tracks, in the mud, on clay tracks, on asphalt, on indoor tracks, from the 60 on up. I had to be the man on the scene, a bomb thrower.” Injured during the Olympic years, Williams’ last detonation came at the inaugural World Cup, in 1977, in Dusseldorf, Germany, where he won the 100 meters over Borzov and anchored the U.S. to a world record in the 4x100 relay. In the period’s mercenary world of sprinting, in the aftermath of world attention on Tommy Smith and John Carlos, and shoe companies starting to seek stature with the particular feet in their custom spikes, the canny Williams broke ground in being able to manipulate a porous and poorly regulated system to his advantage. Williams, who graduated San Diego State the previous year, had an instinct for gainful, lucrative alliances while, at the same time, showing other athletes how to work the system. “I was faster off the track than on it,” he told me with pride. At Kingston, in what was heralded as “The Fastest Night in Track and Field,” before 37,000 fans, it was not Williams but a middle-distance runner who stole the headlines with a world record mile. Filbert Bayi of Tanzania, after a 23-hour trip from his homeland, defeated Marty Liquori and Eamonn Coghlan in 3:51.0, to shave one-tenth from Jim Ryun’s eight-year-old mark. That year was Sands’ best by far. In addition to his NCAA indoor title and domination in Jamaica, Sands captured the Pan Am Games 200 bronze in Mexico City, in 20.92 into the wind (in a Pan Am tune-up meet, Sands won the 200 in his fastest time, a wind-aided 20.58) and also placed fourth in the 400. He also clocked his 100 best of 10.1, though wind-aided, in Nassau. In the one ’75 race that finally put an international title into his hands, Sands had to capitalize on his foxhole grit. It was the Central American and Caribbean championship in Ponce, Puerto Rico. The facility was a dirt track around a baseball field. It poured, drenching the track and delaying competition. Finally, officials got the idea of attempting to dry the track by pouring gasoline on it — to burn away the water. Instead, Sands remembered, “they put the track on fire.” When all was said and done, Sands, from lane eight, went out on a track spewing like a chemical dump and won the title in 46.5 — the meet’s first ever gold medal by a Bahamian athlete. After a down period, Sands tried a comeback for the 1980 Moscow Olympics. But with the U.S.-led boycott, no way to earn a living through track, and continuing frustration with the bureaucratic coaches, Sands decided to retire at 28. While working for Bahamas Airlines and the Ministry of Tourism, Sands began his steady climb to one of the foremost figures in track and field. He was named head of the Bahamas Athletics Federation, a post he held in two installments for about 10 years, and also served four years as vice-president of the Bahamas Olympic Committee. “Even when he was 16,” said Levine, “Mike told me he wanted to eventually go home and serve his people.” “If I have the opportunity,” said Sands, “I want help others. I want to make a lasting impression.” Levine and his family attended Mike’s wedding in the Bahamas 40 years ago. Mike and his wife, Terri, a retired banker, have five children (and nine grandchildren), one of whom almost changed her name because of a hurricane. It was a daughter, Michelle. When, in 2001, Hurricane Michelle ripped the roof off the Sands’ home, it had a dramatic effect on the young girl, who experienced panic attacks when storms forced her and classmates to take shelter under desks at school. Michelle decided she no longer wanted her name. That phase passed. There were no more hurricanes named “Michelle.” But there were still hurricanes to brace for. During another destructive storm, in which neighbors had to evacuate their homes with standing water, Mike and Terri served as a kind of Red Cross depot, with more than 25 people, adults and children, clutching to safety on their stairwells. Merging his commitment to the Bahamas and the wider world, Sands was elected to the NACAC presidency in 2019 and re-elected in 2023. He’s often flying off to Bogota or Rio or Mexico City to work with national governing bodies to develop programs, drum up financing, fine-tune competitions, or see that compliance standards are maintained.

NACAC’s member nations include the U.S. and Canada. It is one of six regions — Europe, Asia, Africa, Oceania and the United States (which also functions as an independent “region”) are the others — with 214 nations in all. As the NACAC head, Sands has a seat on the 26-member World Athletics Council, headed by its president, Sebastian Coe, the two-time Olympic 1,500 champion and former world record holder in the 800 and mile, from Great Britain.

Sands puts that integrity to use in Nassau’s inner-city, where he mentors young men, trying to help them resolve conflict. In deference, the people call him “Pops” or “Senior Man,” a latter-day role that Sands relates back to his days in Sheepshead Bay. After eight years, Levine left Sheepshead to coach at another school and then at two small colleges. In 2008, Sheepshead (which had a track by then) won the boys 4x100 relay at the outdoor nationals in Greensboro, N.C., and months later I visited the school for a story about the team’s sprint and hurdles corps. In 2016, with many large high schools being re-structured, Sheepshead closed and was broken up into smaller schools and re-named, Frank J. Macchiarola Education Complex, after a former city schools chancellor. Larry David could have had a ball with that one. But things change. When I see Mike, with his aristocratic bearing, awarding medals at the Olympics and world meets, I think of the young man who sat at my kitchen table, filling our apartment with his magnanimous presence. The song he sings, lodged in the chambers of his mind. Just listen. In Nassau’s track stadium, Sands’ life-size image has been added to the country’s “Legends’ Walk of Fame,” an installation assembled in a ceremony last year. Levine, and his wife, Ronnie, were present for the festivities, at Mike’s invitation. But, when Mike took the stage, no one could have known what would happen next. Mike looked out to the gathering with his accustomed serenity, his prepared thank-you remarks in front of him. Then, overwhelmed with emotion, Mike spontaneously called Stuie up to the podium and put his arm around him. Addressing the crowd, and Stuie personally, Sands went off-script and said: “If not for this man, I would not be who I am today.” Tears flowed, a gushing traced to Brooklyn, where the subway roared with symphonic deliverance. # The author and journalist Marc Bloom, whose career spans 60 years, contributes historical stories. His books include “God on the Starting Line,” about his coaching at a Catholic school, and “Amazing Racers,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty. In 2022, Marc was inducted into the Van Cortlandt Park Cross Country Hall of Fame. More news |

If Mike needed something, the “Team” sprang into action. Stu Warner, the philosopher and marathoner, treated Mike to burgers at a popular Sheepshead Bay restaurant. I was newly married and living in the area. Every so often my wife and I would get a call from Mike at a phonebooth downstairs. Could he come up and say hello? We’d go get hero sandwiches at the local deli and devour them. At one point, Mike got an after-school (or, rather, after-practice) job at a supermarket, stretching his day from 6 in the morning to 11 at night.

If Mike needed something, the “Team” sprang into action. Stu Warner, the philosopher and marathoner, treated Mike to burgers at a popular Sheepshead Bay restaurant. I was newly married and living in the area. Every so often my wife and I would get a call from Mike at a phonebooth downstairs. Could he come up and say hello? We’d go get hero sandwiches at the local deli and devour them. At one point, Mike got an after-school (or, rather, after-practice) job at a supermarket, stretching his day from 6 in the morning to 11 at night. Levine piled on more strength, training Sands like a miler as indoors began. In an early meet, another bold move: Sands slated to lead off a two-mile relay at the Armory. The reluctant quarter-miler now in the half! When his sprint buddies from Boys High got wind of it, they broke out in laughter.

Levine piled on more strength, training Sands like a miler as indoors began. In an early meet, another bold move: Sands slated to lead off a two-mile relay at the Armory. The reluctant quarter-miler now in the half! When his sprint buddies from Boys High got wind of it, they broke out in laughter.

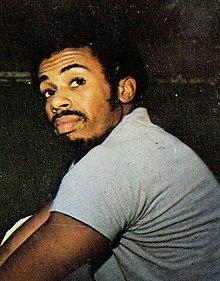

Perhaps that was just so much bait for his old nemesis, Steve Williams (pictured), who by now was ranked the No. 1 sprinter in the world and labeled “the world’s fastest human.”

Perhaps that was just so much bait for his old nemesis, Steve Williams (pictured), who by now was ranked the No. 1 sprinter in the world and labeled “the world’s fastest human.”

Shortly, when the

Shortly, when the